As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

The concept of pasture management, often referred to as rotational grazing, began with the French farmer Andre Voisin in the 1950s. While Voisin called it Rational Intensive Grazing, the approach to rotational grazing is similar today.

Table of contents

What is rotational grazing?

So what is rotational grazing? Rotational grazing is the process of moving a group of livestock through paddocks (small sections) of high quality pasture, with the density of livestock high enough that they are able to eat all of that area’s pasture in a uniform manner before they move on to a fresh section.

Commonly, the time in the paddock will vary from a half day to a few days. The paddock is allowed to rest and regrow before livestock will graze it again.

From a historical context, rotational grazing of livestock is mimicking the natural migrations and grazing of bison and other native wild ruminants before our prairies and grasslands became less wild and more populated with settlers. As a herd, bison would graze from one area to another seeking out new forage to eat.

Continuous grazing

Often the term “grazing” may be confused with continuous grazing. While grazing is a general term, continuous grazing and rotational grazing are two very different management practices of both pasture and livestock.

Continuous grazing is the concept of putting your livestock in a pasture, with access to the entire pasture for the whole grazing season or until everything is completely eaten. This approach does not include the practice of using paddocks with the livestock grazing in that area for short periods of time, typically a few days at most, and followed with at least 45 days of rest.

Synonyms for grazing

Synonyms for grazing or other common terms for rotational grazing include:

- Managed grazing

- Managed intensive grazing

- Mob grazing

- Regenerative grazing

- Holistic grazing

- Adaptive grazing

- And others

These grazing terms are very similar. In some cases, it’s just a difference in approaches with the time livestock spend in a pasture and the stocking rate (number of animals in a paddock).

The concept is the same, paddocks, short duration on that paddock, and adequate rest and regrowth of the paddock before livestock return to graze again.

Here’s a little more information on several of the more popular rotational grazing terms and practices:

Simple Rotation

The simple rotation is rotational grazing at the very basic level. Pastures are typically split into four paddocks and animals are moved through one week at a time, with stock returning to a paddock at 30 days.

This approach is often the first place graziers usually start.

Intensive Grazing

Intensive grazing, or also called managed intensive grazing or management-intensive grazing (MIG) as coined by Jim Gerrish. This type of grazing practice includes daily moves to new paddocks, with at least one paddock per day of recover. So in a basic sense, a recovery time per paddock could be 30-45 days, but even 60 days or longer. This is dependent upon your climate and where your pastures are at in the growing season.

Moving from weekly moves to daily moves can potentially attribute to improvements, such as livestock being more content, stock not getting out, improved weaning weights, increased conception rates, paddocks have more uniform growth, and fewer weeds (Strickler, 2019).

These improvements are likely tied to the fact that livestock are getting “new” feed daily, which means they have access to more consistent high quality feed, vs a zig zag of quality from the beginning of their time in a paddock to the last day.

Mob Grazing

Mob grazing is another approach, where livestock are moved daily or even several times a day. Paddocks are left to rest for long periods of time, often up to a year.

Adaptive Grazing

Adaptive grazing is a rotational grazing approach that’s focused on being flexible with your current herd needs, growing season point, weather patterns, and so on.

It’s based on pounds (of animals) instead of per head on a paddock. Paddocks aren’t preset in size throughout a grazing season. It’s based on being adaptive to your current needs and situation.

Regenerative Grazing

Regenerative grazing is another name for rotational grazing. It’s one of many regenerative farming practices that can be a tool farmer and ranchers can use to manage their land and livestock. The use of regenerative really has been added to fit into the nomenclature of of regenerative agriculture.

Benefits of rotational grazing

The benefits of rotational grazing are numerous for both your livestock and your land.

- Spreads natural fertilizer of fertility-building manure in a more consistent approach than continuous grazing

- Decreases soil erosion since there’s always plant cover

- Helps reduce weeds, since livestock can’t be overly picky when grazing a small section of pasture (paddock)

- Strengthens root systems by not letting livestock graze plants down the ground

- Allows legumes to compete against grasses, which are typically faster growing

- Increased pasture resiliency with forage production during extreme conditions, such as drought or excessive rain

- Increases yield potential of pastures

- Minimal or no synthetic inputs or tillage

- Increased plant and wildlife diversity, and microbial life in the soil

- Reduced operational expenses for farm and ranch families

Stocking Rates

Stocking rate is the technical term for how many animals per acre or how many head of livestock your land might handle.

You’ll need to know this rough number as you plan for your grazing season.

Stocking rates are based on your average pasture yield (or measurements) per acre, estimated grazing season in days, average weight of your livestock, and including young stock, for the season.

You can learn more about how to calculate how many goats per acre your land can support in this article. Numbers can also be substituted for sheep as well.

Paddocks

Paddocks definition: A small section of your pasture where your livestock graze for a set period of time.

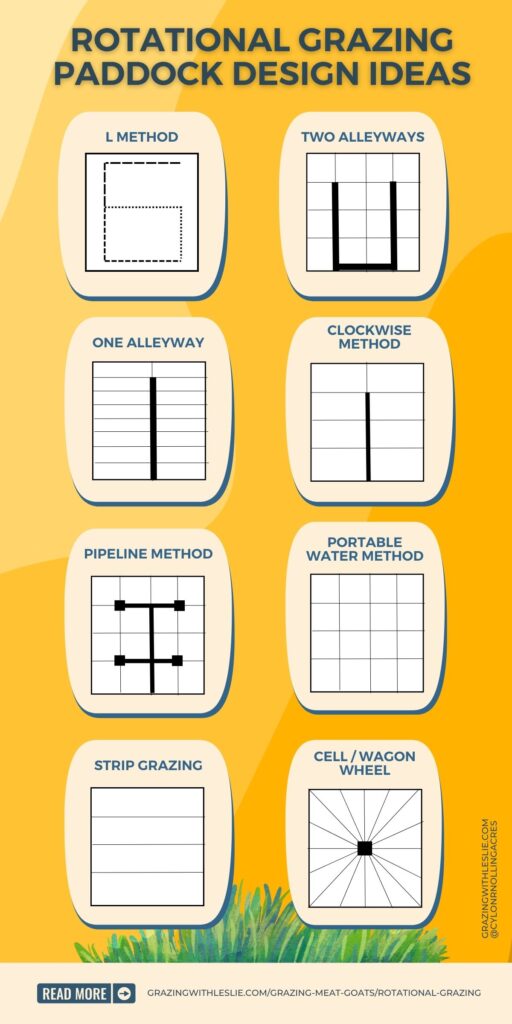

Rotational grazing paddock design

There are several different types of rotational grazing paddock designs.

The paddock design you choose to use will be dependent upon your pasture set up, access to water, soil type, other land constraints and other factors unique to the context of your farm or ranch and even livestock.

Additionally, you’ll want to think about how you’ll move your livestock through the land they’ll graze and where they’ll end up or where you want them to come back to. Setting up paddocks for easy transition from one paddock to the next will help with making the moves easier to manage with moving livestock and any related equipment and supplies.

Keep in mind flexibility for your paddock design, this way you can adjust your portable fencing based on forage growth, for example when you have the spring flush or when growth slumps in mid summer, or if you change your herd size, increasing or decreasing.

My preference is to work within one large pasture, and subdivide it into smaller paddocks, keeping in mind where and how I want to move my goats and sheep while they graze.

It can help to print out aerial photos of the land you’ll be grazing to pencil out your paddocks. You can access maps through the USDA Soil Survey portal.

L method

Set up a pasture with portable fencing, such as electronet or polywire in two L’s with the top “L” upside down on top of the bottom “L”. This will leave a tail at the top to build the next paddock with a third fence. You can keep moving your herd this way throughout a pasture without ever having your animals outside of a fence.

Two Alleyways

Pasture is split into multiple paddocks with access to each paddock by way of two alleyways or animal walkways. The alleyways are typically built to handle regular animal traffic no matter the weather.

Water is available in the alleyway.

One Alleyway

Pasture is divided by one alleyway/walkway through the center with access to paddocks on both sides. The walkway is built to handle frequent animal traffic.

Water is accessed through the alleyway.

Clockwise Method

The pasture is divided down the center with cross fencing, with paddocks running the opposite direction. Animals are moved through in a clockwise direction (or counterclockwise if you wish), and will return to the entrance of the pasture where they began once the full rotation is complete.

Water access can be strategically located along the cross fencing by means of a pipeline or larger fill tank.

Pipeline method

Build a paddock grid within your pasture based off your water tank points (by way of a pipeline, above or below ground).

Portable Water Source Method

Build paddocks within your pasture that makes sense for moving livestock from one point to another. A portable water holding tank moves along with your herd to fill the drinking tank.

Strip Grazing Paddocks

Paddocks are built in long strips where animals move to new paddocks. Typically the back fence is left open so animals can return back to the water source.

Cell Center or Wagon Wheel Paddock

Begin at the water source, and then move the animals away to new paddocks on a regular basis, with no back fence until you’ve reached the end of the pasture or are too far away from the water source.

Adapted from the West Central Forage Association.

Rotational grazing diagram

Here are rotational grazing diagrams for each paddock design:

Timing to graze a paddock

When it comes to rotational grazing, timing is everything. Timing falls into two categories.

- Time livestock spend in a paddock

- Time for paddock rest before livestock can return to the pasture to graze

Time livestock spend in a paddock

The timing for livestock spent in a paddock can range from a few hours to a few days. Most grazing experts and research shows that time spent rotational grazing in one paddock ideally should be no more than one day to maximize feeding your livestock the most optimal quality pasture.

This time period can be view as time spent in a paddock, but it’s probably better to view it as the time needed to be in the paddock based on your observations of the livestock’s consumption of the pasture (which generally speaking is eat half, leave half).

Less time spent in one place also reduces the overall animal impact on the plants, whether that’s from trampling or eating. This allows the plants to focus their recovery above ground rather than working harder to also rebuild its root structure underground which tends to get more damaged when plants have more “damage.”

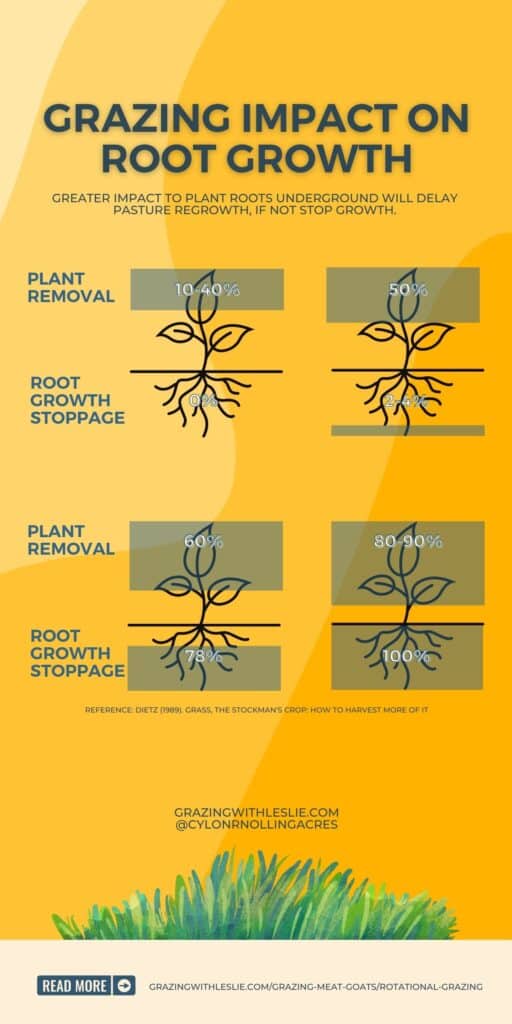

A USDA plant clipping study showed the growth of the plant above ground is comparable to the root growth. When the top of the plant is removed, it will have an impact on the root growth. In fact, when too much is taken from the plant by grazing or even cutting the roots will stop growing and limit how much future growth it will have going forward (Crider).

Another USDA study (Dietz) showed the amount of plant material removed compared to the impact on rooth growth stoppage:

- 10-40% plant removed: 0% root growth stoppage

- 50% plant removed: 2-4% root growth stoppage

- 60% plant removed: 78% root growth stoppage

- 80-90% plant removed: 100% root growth stoppage

Outside of the benefits to plant regrowth, the time spent on pasture for sheep and goats helps with managing internal parasite issues. For small ruminants, research has show that after 3-4 days sheep and goats run the risk of reinfecting themselves with internal parasites since that’s the time it takes for larvae to hatch (Zajac).

Time for for paddock rest

The other key factor in timing for rotational grazing is allowing enough time to “rest” for each paddock grazed before animals return.

The rest time allows for plants to regrow not only above ground, but also expand their root structure below ground. This work below ground is often overlooked, but very important since it contributes to increasing soil microbe life and improving soil structure for water infiltration and retention.

The rest should also allow for enough time for the internal parasite life cycle to end before animals return to the paddock. For example, with the sheep and goats we graze on our farm, we don’t return to a paddock any sooner than 45 days to allow for the parasite cycle to stop, which is usually 30 days.

How much time is the right amount of time for letting paddocks rest? It really depends on your context of your farm or ranch, including your climate and condition of your soil and forages.

A good rule of thumb is a minimum of six weeks, or a month and a half of rest (Beef Cattle Research Council). If your region has less rainfall or other factors related to the context of your farm and ranch, may merit a longer rest period.

Observing pasture availability

While livestock are grazing it’s important to also observe how much available pasture they have in the paddock where they’re located. Keep in mind how much was in the paddock to start.

A good rule of thumb is to take half and leave half of the standing pasture.

Cool season forages should be grazed no lower than 3-4 inches, while warm season forage should be grazed now lower than 6-12 inches (USDA NRCS).

These numbers can serve as a guide as you watch what’s available. Then, combine this with timing spent in a paddock and you can start to make adjustments to your paddock size throughout the season based on your forage availability, growth and consumption by your livestock.

Avoiding over grazing

When grazing livestock it’s important to avoid over grazing a paddock and causing too much damage to the plants in your pasture.

Over grazing happens when livestock are in one place for too long, or return back to a paddock too soon. It is about the length of time in a paddock vs. the number of animals.

For example, one goat or sheep on one acre of pasture all season, continuously grazing, can kill hundreds of plants. However, if 50 goats or sheep graze that same acre for one day they won’t kill any plants in the pasture.

Equipment and Supplies Needed

With rotational grazing livestock, you’ll also need the following supplies:

- Portable electric fencing

- Energizer to power the portable fence

- Water with water tank

- Shelter or cover for shade

- Access to minerals

Grazing Tools

- Grazing stick. This yardstick type tool is used to measure forage height and density to help determine the dry matter available for grazing in a paddock.

- Grazing apps. Technology to track and manage grazing paddocks and livestock. A few examples include Mia Grazing, Pasture Map, and Agriwebb

- Grazing chart. A paper chart to track livestock grazing moves by paddock throughout the grazing season

- Brix refractometer. A tool to measure the Brix levels in pasture plants to determine the nutrient levels at a certain point of time. (affiliate link)

- Fault finder for troubleshooting electric fence issues

Grazing animals

Grazing animals are classified as ruminants, which are hooved mammals that have a four compartment stomach (rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum). This digestive system allows them to convert fibrous plants to ferment into energy.

Ruminants can be both wild animals, such as white tail deer and antelope, and domesticated livestock, including cattle, sheep and goats.

In contrast, monogastric mammals include domesticated livestock, such as hogs and poultry. Humans are also monogastric.

Grazing with Small Ruminants

On our farm Cylon Rolling Acres, we are rotational grazing goats and sheep. We move our livestock very 1-3 days and don’t return to a paddock any sooner than 45 days.

This grazing season I’m looking at incorporating longer rest before returning to a paddock in our pastures.

This approach has been in place to help manage internal parasites with our goat and sheep grazing, but also with the idea of improving the quality of our soil and pastures, including the legumes, forbs, and grasses.

We are also using portable and permanent fence options for grazing our goats and sheep.

Related blog posts

References

- Andre Voisin, Wikipedia

- Crider, J.F. (1955). Root growth stoppage resulting from defoliation of grass. UDSA Technichal Bulletin. 1102: 23 p.

- Dietz, H. (1989). Grass, the Stockman’s Crop: How to Harvest More of it. USDA.

- Grazing Guide, GrassWorks Inc. (February 2010).

- Grazing Benefits. Pasture Project. Wallace Center at Winrock International.

- Grazing-Stop Heights Are Important. USDA NRCS.

- Pasture Planner. (2017). West-Central Forage Association.

- Pasture 101, Managing and Planning Grazing. Alberta Beef Forage and Grazing Centre.

- Regen Ag 101. Understanding Ag. (2023).

- Undersander, D., Albert, B., Cosgrove, D., Johnson, D., and Peterson, P. Pastures for Profile: A Guide to Rotational Grazing. 2014. University of Wisconsin-Madison. Accessed at https://learningstore.extension.wisc.edu/products/pastures-for-profit-a-guide-to-rotational-grazing-p96

- Zajac, A. 2013. Biology of parasites. In: Proceedings of American Consortium of Parasite Control Tenth Anniversary Conference. American Consortium for Small Ruminant Parasite Control, Fort Valley, Georgia. Available at https://wormx.info/2013-conference

Under heading ‘Time Livestock Spend in Paddock’ , you mention the average for grazing is approx 1 day. Under the heading ‘Time for Paddock Rest’ you state that you don’t revisit a paddock for approx 6 weeks. Does this mean that you have 40+ paddocks set up?

Yes basically it would end up being 40 paddocks before returning to a paddock. Depending on your available pasture and portable fencing options, you might be able to get to this extended rest time by grazing in wooded areas, hayfields, your yard even!, or other areas where you might not traditionally graze to give the pastures adequate rest. I don’t actually set up 40 paddocks at one time. I’m not sure if you were asking this in the question or not, but I’ll touch on it just in case. We’re using portable fencing and creating the new paddocks each move. Good question!

Hi,

hi,

How many square feet does one goat eat per day approximately?

I know there is lots of variables, just wanting to get an idea for where to start space and quantity wise…. As we are looking to buy land but can’t afford q huge section so looking at maybe 3-5 goats. Planning to have 50-60 paddocks. Live in a very fertile part of the world, New Zealand, mild climate

It really varies on the time of year, quality of the pasture, and the age of the goat. But, if you the goats per acre calculator I have – it can be helpful to get a rough estimate of what makes sense for your particular location/setting. https://grazingwithleslie.com/grazing-meat-goats/qa-june8/